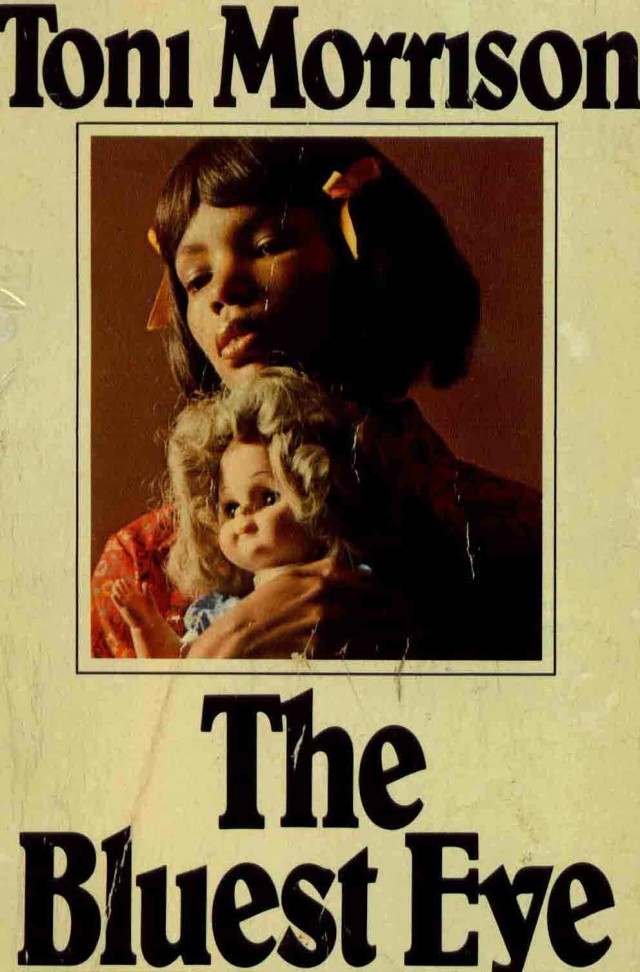

The Bluest Eye

by Toni Morrison

"Contemporary Reviews" Review

Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye,” received mixed reviews when it was initially released for publication in 1970. Many felt it was inappropriate for students due to the content and themes dealing with child abuse, molestation and incest. Others found the controversial content pivotally relevant in the fight to end internalized racism of the self.

There aren’t many reviews or literary criticism essays from 1970 available online, however the most through and positive is arguably from The New York Times: Books of the Times, by cultural critic John Leonard. Taking Refuge In ‘How’ (New York Times 1970) is a positive review that focuses on “how” the events of the book happened to Pecola Breedlove, including the hardships that both of her parents faced, as well as looking at what happened to the supporting characters like Claudia and Frieda MacTeer during the same year. Leonard, like Claudia in the text primer, argues that if we can understand the “how,” then that understanding answers the question of why this happened.

“Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” is an inquiry into the reasons why beauty gets wasted in this country. The beauty in this case is black; the wasting is done by a cultural engine that seems to have been designed specifically to murder possibilities; the “bluest eye” refers to the blue eyes of the blond American myth, by which standard the black-skinned and brown-eyed always measure up as inadequate. ” (Taking Refuge In ‘How,’ 1970)

Similarly, according to Carl D. Malmgren in “Texts, Primers and Voices in Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye,” (Malmgren, University of New Orleans 2000, PG 256), the form of the text through it’s break down of seasons and primers (the intro’s and descriptions of each season), as well as the differing perspectives from which the story is related, break down the “how to why” theory for each character. We begin to see Leonard’s cultural engine of waste, through the abandonment of Cholly by his biological father and then mother, and then the eventual untimely death of his aunt. The wasting that is done by the cultural engine, which we can interpret to mean everyone and everything in America at this time because each character is a victim in some sense of the word; of society and circumstance. The entire country was set up on inequalities that designed “the murder of possibilities,” meaning the growth of happy, healthy African American children. Instead they were growing up with out self-esteem that was replaced by an ingrained self-hatred, for example Pecola praying for blue eyes to become the stereotypical American standard of beauty. Or we could look at Pauline’s loss of self, she used to love to cook and clean. She would take pride in her home, but her identity crumbles around her due to lack of familial support once she moves away from Kentucky to Ohio.

Leonard goes on further to touch on the aesthetic quality of Morrison’s writing, saying, “I have said “poetry.” But ‘The Bluest Eye’ is also history, sociology, folklore, nightmare and music. It is one thing to state that we have institutionalized waste that children suffocate under mountains of merchandised lies. It is another thing to demonstrate that waste, to re-create those children, to live and die by it. Miss Morrison’s angry sadness overwhelms.” Interestingly enough Morrison, according to The Paris Review, “detests being called a ‘poetic writer.’” (Toni Morrison: The Art of Fiction No. 134, The Paris Review 1993) However, it is her style and unique voice—it’s rhythm and cadence that appeals to Leonard. Her writing brings about that authentic, emotional reaction that overwhelms him.

Other than Leonard’s review, I couldn’t locate other reviews from the period when The Bluest Eye was published, most likely caused by the limited release at the time and then subsequent result of being out of print by 1974.

Due to the fact that Morrison was a well known, and revered author, receiving national and international recognition for her other works, she won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1993, which is the same year The Bluest Eye was published again. Public perception of the book began to change and eventually in 2000 Oprah Winfrey publicly supported and backed the book by making it a featured book in Oprah’s Book Club.

“Oprah has not chosen [four] Toni Morrison books because she and Mr. Morrison are friends, but because Oprah feels that ‘Toni Morrison is the best writer, living or dead, and I love her work’” (The Oprah Affect, State University of New York Pr, 2008)

Today, the book is considered by academia to be one of the most relevant and influential works because of Morrison’s ability to deconstruct the stereotypical and superficial white ideals of beauty. There are still institutions who challenge the book or attempt to ban it, however, generally it is regarded a work of art. It has been adapted into plays and performed at Steppenwolf Theater Company, and according to Randy Gener of American Theatre, he believes it’s a not a children’s story, for him, Pecola’s story is very much adult in nature and thematically. He implies it’s perfection and suitability for adult audiences rather than a story for children, because of the overt and occasionally nuanced themes of abuse, and how self-destructive racism can be. (Front & Center: Mad Like Shirley Temple’s Eyes, 2005) Steven Suskin is likely to agree with Gener, he challenges the performance saying it’s definitely not for young teens, even in the age range of 14 (3 years older than Pecola in the story) because of the graphic rape scene in the performance. (Variety: The Bluest Eye, 2006)

Additionally, most reviews for Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, tend to come out in November, which seems in accordance with Claudia’s narration of Pecola’s story starting in the Fall after the original primer. Regardless of when it’s read, it is a work that has the power to change social consciousness about issues that persist in relevance still to this very day.

Works Cited

(Taking Refuge in ‘How’)

Leonard, John. “Books of the Times.” New York Times 13 Nov. 1970. Web.http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/01/11/home/morrison-bluest.html

(Malmgren, University of New Orleans 2000, PG 256)

Malmgren, Carl D. “Texts, Primers and Voices in Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye.” Vol. 41, NO. 3.Spring 2000 (2000): 256. University of New Orleans. Web.

(Toni Morrison: The Art of Fiction No. 134, The Paris Review 1993)

Shappell, Ellissa, and Claudia Brodsky Lacour. “The Paris Review.” Paris Review. The Paris Review, 1 Jan. 1993. Web. 7 Oct. 2014.

(The Oprah Affect)

Farr, Cecilia Konchar. The Oprah Affect Critical Essays on Oprah’s Book Club. Albany, NY: State U of New York, 2008. Print.

(Front & Center: Mad Like Shirley Temple’s Eyes, 2005)

Gener, Randy. “Mad Like Shirley Temple’s Eyes.” Front & Center. American Theatre, 6 Nov. 2005. Web. 7 Oct. 2014.

(Variety: The Bluest Eye, 2006)

Suskin, Steven. “The Bluest Eye.” Variety 3 Nov. 2006: 57. Web.

< http://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/detail/detail?vid=21&sid=df1999ef-c956-4a28-b55a-ec73a8669190%40sessionmgr112&hid=113&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3d#db=f3h&AN=23115173>

Discussion Questions

What is the significance of the Dick and Jane books? Why does Morrison use them to introduce specific sections?

How is feminine sexuality discussed in the novel? Is it different for young girls and older women?

What literary techniques does Morrison use to discuss race relations and racism in the novel?

Who does the novel attempt to demonize and who does the novel attempt to portray as heroic? Why?

What structures exist in the 1940's that support the existence of racism, poverty, sexual abuse & violence?

Sources

Baldassarro, R. Wolf. "Banned Books Awareness: "The Bluest Eye"" Banned Books Awareness. Bannedbooks.world.edu, 10 Sept. 2013. Web. 04 Oct. 2014.

“Chloe Anthony Wofford.” Bio. A&E Television Networks, 2014. Web. 04 Oct. 2014.

Gates, Sara. "Ohio Schools Leader Calls For Ban Of 'The Bluest Eye,' Labels Toni Morrison Book 'Pornographic'" The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 13 Sept. 2013. Web. 04 Oct. 2014.

“Toni Morrison (American Author).” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 04 Oct. 2014.

“Toni Morrison – Biographical.” Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB, 2014. Web. 04 Oct. 2014.